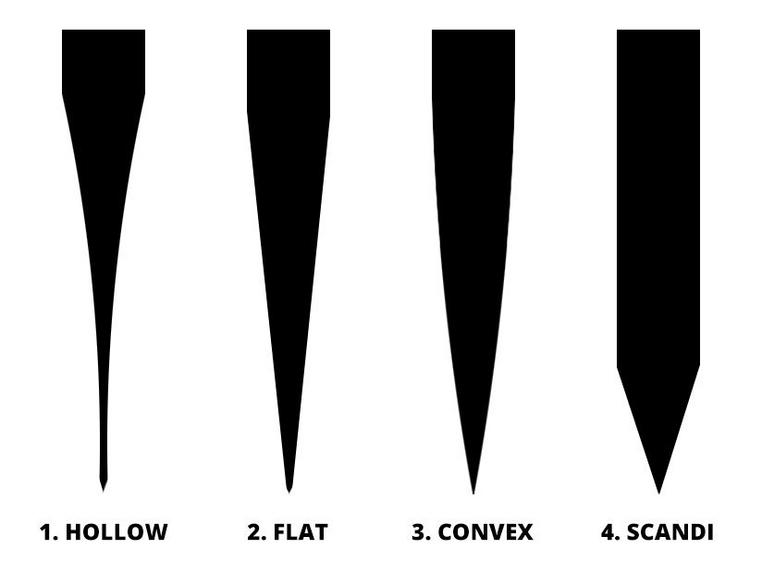

Knife grinds: flat grinds, hollow grinds, convex grinds and scandi’s

When it comes to knife grinds you often immediately think of the sharp edge. Makes sense, because the edge is also sharpened. But that is not what we are talking about right now. After all, we are going to talk about knife grinds.

A knife grind is a type of grind that makes the blade thin enough to cut with it. You might imagine that a piece of 4 mm thick steel with only a sharp edge won’t get you very far when you use it. In the end you will be left with a wedge effect rather than that you actually cut through fibres. That is why a knife needs a grind.

How thin is it behind the edge?

In general the following applies: the thinner the blade, the better it will do what it is supposed to. We do, however, have to mention that a thinner edge is also more vulnerable. For that reason you need to check per type of steel and purpose if the knife can handle it. After all, a classic straight razor is incredibly thin and amazing to use, but as soon as you use it for woodwork you won’t have a knife left when you are finished. And vice versa. A thick survival knife is great to split wood, but cutting through an apple without splitting it is nearly impossible.

As a result one often speaks of ‘how thin a knife is behind the edge’. From it you can deduce how well it will do what it is supposed to and how much it can handle.

The different knife grinds

That grind can be carried out in many different ways. All these options have their own specific features. We would love to tell you more about the most common grinds.

Hollow grind

As the name might already suggest the hollow grind is hollow. Traditionally speaking a hollow grind was applied by pushing the side of the blade to a large, spinning, grinding wheel. Because of the curve of the stone a hole would emerge which would stretch out over the entire length of the blade.

The advantage of a hollow grind is that the edge can become incredibly thin. It is for a reason that almost all classic straight razors have a hollow grind. In addition, it is easier to sharpen a hollow grind blade without the edge getting thicker behind the edge.

A disadvantage of the hollow grind is that the edge can also be a lot more vulnerable. Exactly because a hollow grind can be a little thinner behind the edge you run the risk of breaking it faster. In addition, when you have a thicker blade with a hollow grind you might experience that cutting through cardboard is easy when you use the edge and the incredibly thin part just behind the edge. However, you could also experience that the thick spine of the blade could suddenly act as a blockage when you use it.

Flat grind

By far most knives you come across have a flat grind. A straight, flat grind from the edge upwards. The grind could reach to halfway up the blade, a sabre grind, but also up to the spine, which is when we refer to it as a full flat grind. Practically all normal kitchen knives have this type of grind.

The flat grind has some advantages. After all, it looks nice and sleek, is relatively easy to produce and is nice and strong.

The disadvantage of the flat grind is that it is relatively speaking a little bit thicker behind the edge. In addition, when compared to a hollow grind you cannot sharpen it that often before it will definitely start to get thicker behind the edge. Of course this is relative: we are talking about sharpening the knife hundreds of times.

Convex grind

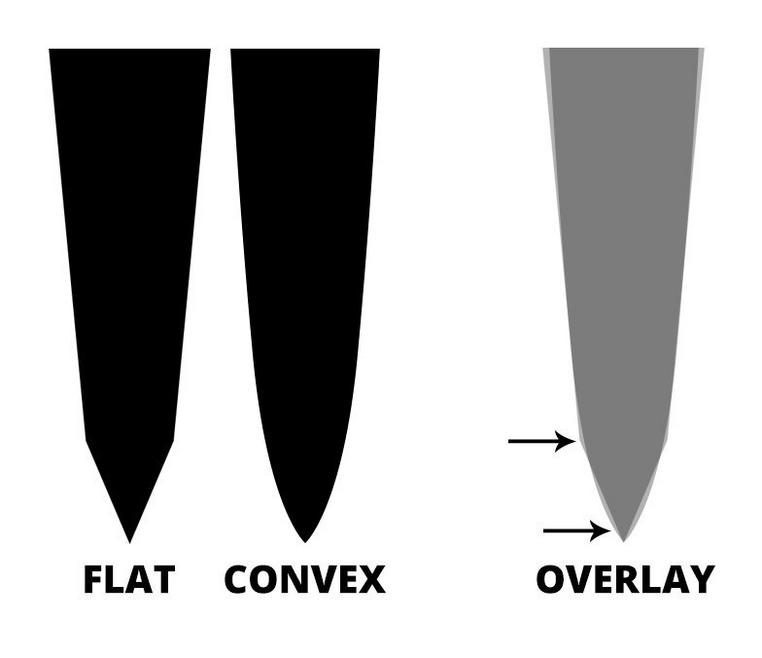

A grind that often leads to questions is the convex grind. Instead of it being hollow this grind is rounded. To achieve this grind one sharpens the blade on a free sharpening belt. Remarkable about the convex grind is that there is no longer a secondary edge, but that the grind is applied up to the cutting edge.

A convex grind has a couple of important benefits. If properly carried out a convex grind knife can have a stronger edge and still cut smoothly. After all, you miss the cornered shoulder of the edge. Difficult to explain, which is why we have made the picture shown above.

You can clearly see that the flat grind has a corner at the edge of the edge. This is the transition from the primary grind or bevel, to the edge. At the same time you can tell that the convex grind is a little thicker behind the edge. A great combination between strength and better cutting performances. Especially when making a feather stick, a true bushcraft technique, you notice the advantage of a convex grind.

There are, however, also disadvantages. For instance, it is tricky to consistently come up with a good convex edge in the factory. In addition, knives with a good convex edge are often a lot more expensive because it takes a lot of manual labour to apply one. There are also a number of people who find sharpening a convex edge incredibly difficult. Stropping is often not a problem, but applying a new edge when using sharpening stones is something a lot of people struggle with. Even though we know that with a little bit of practice it is not that difficult at all.

Scandi grind

The scandi grind comes, as the name might already suggest, from Scandinavia. Here a scandi grind on outdoor knives, hunting knives and bushcraft knives has been the standard for years. A scandi grind is actually one large secondary edge, without any additional frills.

Practical about the scandi grind is that you can easily sharpen it and that it is easy to produce. In addition, a scandi grind is great for woodwork. Because the blade is relatively thick it is incredibly strong and can definitely handle quite a bit.

A scandi grind, however, could also start to work against you if the edge has become too vulnerable after you have sharpened it. In addition, because of the large, wide edge you can see everything you do during the sharpening process. Have you made a mistake? You can immediately tell when you look at that broad edge. And have you made a mistake by chipping the edge? If you have you need to remove quite a lot of material to correct that mistake.

Grind and type of steel: a happy union

For any knife the following applies: an appropriate type of steel should be chosen for the appropriate task. Are you applying an incredibly thin grind to make sure it is absolutely amazing to work with? If you do you also need to make sure you choose a hard type of steel to match the grind. Should the same knife be able to handle its own? If so the steel shouldn’t be that hard as it will immediately crack when you put pressure on it. The balance between the two needs to be perfect to make sure the knife will perform as it should.

Does the type of grind represent the quality?

It is absolutely not the case that one type of grind is always better than the other. You could, however, state that a type of grind is better for a specific purpose. For instance, we believe the scandi and convex grind to be perfect for woodwork and bushcraft purposes. At the same time, flat grinds are perfect for kitchen tasks. Hollow grinds can be drop-dead gorgeous and testify to an enormous amount of production skills. Stunning on an EDC or a gentleman’s knife. At the same time there are examples of all versions that prove their use in a different category. In the end the type of grind therefore doesn’t say that much about the quality of the knife. The quality of the grind, however, does!

?%24center=center&%24poi=poi&%24product-image%24=&fmt=auto&h=490&poi=%7B%24this.metadata.pointOfInterest.x%7D%2C%7B%24this.metadata.pointOfInterest.y%7D%2C%7B%24this.metadata.pointOfInterest.w%7D%2C%7B%24this.metadata.pointOfInterest.h%7D&scaleFit=%7B%28%24this.metadata.pointOfInterest%29%3F%24poi%3A%24center%7D&sm=c&w=1016)

?%24center=center&%24poi=poi&%24product-image%24=&fmt=auto&h=490&poi=%7B%24this.metadata.pointOfInterest.x%7D%2C%7B%24this.metadata.pointOfInterest.y%7D%2C%7B%24this.metadata.pointOfInterest.w%7D%2C%7B%24this.metadata.pointOfInterest.h%7D&scaleFit=%7B%28%24this.metadata.pointOfInterest%29%3F%24poi%3A%24center%7D&sm=c&w=1016)